FOCUS IN/ON - William Gropper

Gropper As a Social Artist

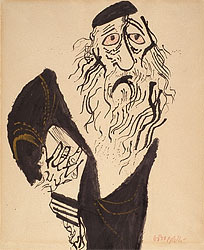

William Gropper, 1897-1977 The Wanderer, c. 1960 Ink with wash on paper, 16" x 14" Hillstrom Museum of Art, gift of Reverend Richard L. Hillstrom ('38)

Gropper then entered the period of his career in which he became known as one of the most prominent, socially minded artists of the time. He was associated with a number of liberal publications, including the New Masses and the Yiddish publication Freiheit, and eventually he drew for more mainstream magazines such as Esquire or Vanity Fair. He devoted much effort to the troubles of the unfortunate or oppressed and to social situations in general. In 1927 he and his wife Sophie traveled to the Soviet Union, along with authors Theodore Dreiser (1871-1945) and Sinclair Lewis (1885-1951) and others, to mark the tenth anniversary of the establishment of the Soviet Union following the Russian Revolution. During their prolonged stay, the artist made many drawings, some of which appeared in Soviet newspapers and a group of over fifty of which were published in 1929. In 1937 Gropper was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship, which allowed him to travel west to witness the Dust Bowl. From this experience, he published a series of insightful drawings with sympathetic captions that appeared in The Nation later that year.

Perhaps Gropper's most infamous drawing from this period, one that caused an international fracas, appeared in Vanity Fair in August 1935. The cartoon was part of a series suggested by editor Frank Crowninshield in which several impossible situations would be depicted, including William Randolph Hearst becoming American ambassador to the Soviet Union, the King of Italy berating Mussolini, or Japanese Emperor Hirohito being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. The Italian drawing was dropped from the group-a letter from Crowninshield to Gropper indicates concern that Vanity Fair could lose significant business from Italian concerns-but the one of Hirohito was published, and it deeply offended the Emperor and the Japanese government, which demanded an apology. The drawing shows the Emperor decked out in medal-encrusted military regalia, pulling a rickshaw-like cart on which an oversized scroll is carried. The scroll ostensibly represents the Peace Prize, but its form and size combine with the wheels of the cart to make it appear that Hirohito is dragging a cannon behind him. The bellicose actions of the Japanese in mainland Asia, including the invasion and occupation of Manchuria, had brought their warring activities into public discussion well before Japan's entry into World War II.

Gropper refused to apologize for his drawing, and U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull had to explain to the Japanese that he had no control over the press. The Japanese retaliated economically, applying pressure to advertisers in Vanity Fair, and this eventually brought about the demise of the publication. The unrepentant Gropper repeated much of the cartoon's imagery, in a December issue of the New Masses. Here Hirohito wears a single, swastika-bearing medal and pulls another cart, this time with an armed skeleton riding on it, across Manchuria and into China.

In the period leading up to and during World War II, Gropper published many additional works that decried the actions of the Fascists. He began in this time to deal directly with his identity as a Jew. As with many Jewish artists, before the war era, Gropper's art did not particularly reflect an interest in his Jewish heritage (and Gropper never had his bar mitzvah, despite his brief attendance at the Hebrew school). Gropper noted, "Hitler and fascism made me aware that I was a Jew. I think all intellectuals who were never concerned with their faith were thrown into an awareness by these atrocities."

The Hillstrom Museum of Art drawing seems to be related to Gropper's wartime experiences and those that shortly followed the War, as will be discussed below. Gropper's probing of the social and political situation continued throughout the rest of his career, including a heartfelt 1963 painting titled I Have a Dream, of black and white children playing together in a sunny, bright landscape and, near the end of his career, images dealing with Watergate. Always looking for truth through his art, Gropper painted around 1945 a philosophical self-portrait in the guise of Diogenes, who carried a lantern in his quest for an honest man.