Quarterly - FOCUS IN/ON

Eby’s War Experience and His Publication War

- Kerr Eby's Early Life and Training

- Eby's War Experience and His Publication War

- Anti-War Art: An Overview

- Where Do We Go?

- Limiting and Eliminating War: Late 19th and Early 20th Century Efforts

- The Kellog-Briand Pact

- The (Not So) New Order After World War II

- Citizen Movements and Hope

- Suggested Reading

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, Eby, too, became involved. After unsuccessful efforts to obtain a commission as an artist, he enlisted and ultimately was assigned to the 40th Engineers, Artillery Brigade, Camouflage Division, which was sent to the war front where the Division helped to protect the troops. Eby saw much battle action, especially in northeastern France, including at Belleau Wood and Meuse-Argonne, and in 1918, he participated in the battles of Château-Thierry and Saint-Mihiel, which were instrumental in preventing the Germans from advancing on Paris. In addition to his work as a camoufleur, he also made drawings of the images he witnessed on the battlefield. Interestingly, Eby’s cousin Frederick P. Keppel was an Assistant Secretary of War for the United States during this time.

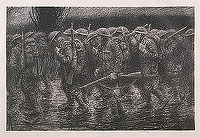

In 1936, concerned about the unstable world situation that would soon lead to World War II, Eby published his book War (Yale University Press, New Haven), which illustrated 28 prints and drawings he had made during his experience in World War I and which included an essay outlining his abhorrence of war and his opinion of its futility and barbarity. The lithograph Where Do We Go? was one of the images in the book, which was dedicated “To those who gave their lives for an idea, the men who never came back.”

Eby’s essay, according to its opening lines, was written “in all humility of spirit, in the desperate hope that somehow it may be of use in the forlorn and seemingly hopeless fight against war.” Eby continued by noting that the images in the book were made from his own “indelible impressions of war,” and were “not imaginary.” He noted further that the “world today [in 1936] is a more savage place than the world of 1914,” and despaired that war—which he characterized as “idiotic”—was heating up yet again. He ended his essay with a special appeal to women, mothers particularly, exhorting them to act and speak up for the protection of the men who would have to fight the impending battles. Eby’s purpose in writing the essay and in publishing his works was not fulfilled, of course, and World War II was not prevented. Although he was himself too old to serve during this Second World War, he served as a correspondent in the Pacific in the combat artist program developed by Abbott Laboratories (which was instrumental in the development of plasma and hired artists to depict its use in the war). Eby again drew images of the soldiers, and he went ashore with the U.S. invading force in Tarawa, where occurred in November 1943 one of the most brutal battles in the history of the Marines. He witnessed much death and, again, recorded his experience in numerous prints and drawings. His friend John Taylor Arms, in a moving tribute to Eby written shortly after his death in 1946, felt that Eby, like the soldiers whose deaths he recorded, had also given his life for the cause, because Eby had contracted a tropical disease while living with the troops for three weeks in a foxhole in the jungles of Bougainville, a condition from which he never recovered and which contributed to his early death.