FOCUS IN/ON - William Gropper

Genocide and Memorialization

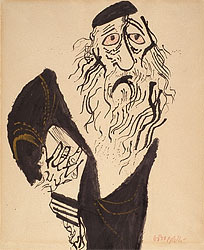

William Gropper, 1897-1977 The Wanderer, c. 1960 Ink with wash on paper, 16" x 14" Hillstrom Museum of Art, gift of Reverend Richard L. Hillstrom ('38)

Why is it important to know about the history of this painting? We live in an age of genocide. The twentieth century was the bloodiest in human history. By one estimate, 170,000,000 people were killed in genocidal slaughter, most often by their own governments. The deaths began in the first decades of the century with the Herero tribe in Namibia at the hands of the German colonizers and the Armenians at the hands of the Turks. It continued through the Holocaust, the Cambodian genocide, and the Rwandan genocide in 1994, when 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus were hacked to death with machetes by government-sponsored Hutus in three months' time, a more efficient rate of killing than the Nazis despite the primitive weapons used. Today, government-funded Janjaweed militia continue to kill innocent Sudanese in Darfur, despite a recent effort to sign a peace agreement; more than 400,000 Darfurians have been killed and two and a half million have been displaced.

In the aftermath of such genocides, the societies involved must come to terms with what happened, with the fact that killers continue to live among them, with the memories that haunt the victims who survived and the relatives of victims who died, with the urgent need to prevent a reoccurrence of genocide. In the post-Holocaust era in Germany, the Germans actually created a specific word to name this process of coming to terms with the past: vergangenheitsbewältigung. Such a coming to terms involves many things: legal procedures in an effort to see that the killers are brought to justice; a transition in national leadership; a process whereby restitution of some kind is made available to survivors; the creation of memorials to assure the memory of the dead. A critical part of this process is artistic production: literature, music, visual arts that memorialize those lost, that help a community to try to understand how such a genocide could have occurred, and that serve as a warning of "Never Again."

William Gropper clearly understood the power of creating a memorial to those who died in the Warsaw Ghetto. By interpreting this painting in the Hillstrom Collection, we as a community acknowledge the history of the Holocaust, the oppression of Jews during the past 2000 years, and the contribution made by William Gropper to memorialization; we also highlight the ability of visual art to capture mourning and rage, to make a political statement, and to help humanity both come to terms with the past and endeavor to prevent such suffering and cruelty from reoccurring.

Scholar James Young, of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, has written extensively on the meaning of monuments and memorials. "The aim of memorials," he asserts, "is not to call attention to their own presence so much as to past events because they are no longer present." Young continues: "Through attention to the activity of memorialization, we remind ourselves that public memory is constructed, that understanding of events depends on memory's construction, and that there are worldly consequences in the kinds of historical understanding generated by monuments." Creating memory of the Holocaust is particularly important as no gravesites of the six million Jews who died exist. We are, in effect, memorializing an absence. Postmodern theorist Jean Baudrillard put it another way: "Forgetting the extermination is part of the extermination itself."

One can imagine that William Gropper hoped viewers of this image would remember that the Nazis annihilated two thirds of Europe's Jewish population while the world stood by. Audiences in 2006 would appropriately recognize in The Wanderer their own responsibility to be aware of social injustice around the globe and to take what steps they can to eradicate it.

Elizabeth Baer, Professor of English

Donald Myers, Director, Hillstrom Museum of Art