Conceptual Framework

Gustavus Adolphus College - Teacher Education Program

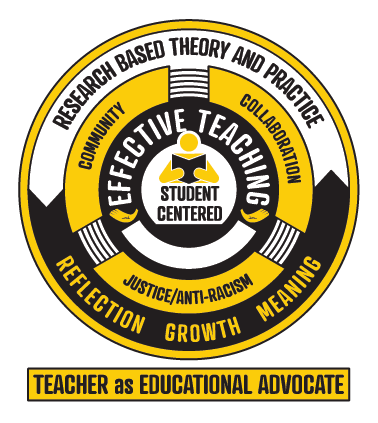

"Teaching as Principled Practice"

Conceptual Framework

The Gustavus Education Department is focused on preparing educators who are equipped to equitably meet the needs of their students in K-12 schools. The department emphasizes the importance of advocacy, cultural awareness, and social justice in

teaching. Its framework incorporates principles such as building supportive communities, promoting collaboration, and embedding values of diversity and belonging into educational practices. Through research-based strategies and reflective teaching, the program aims to equip future educators with the skills and knowledge to meet the diverse needs of students by partnering with local and global schools to provide valuable opportunities for teacher candidates to apply their learning in real-world contexts and empowering educators to create equitable and supportive learning environments for all students.

More about our Vision and Mission.